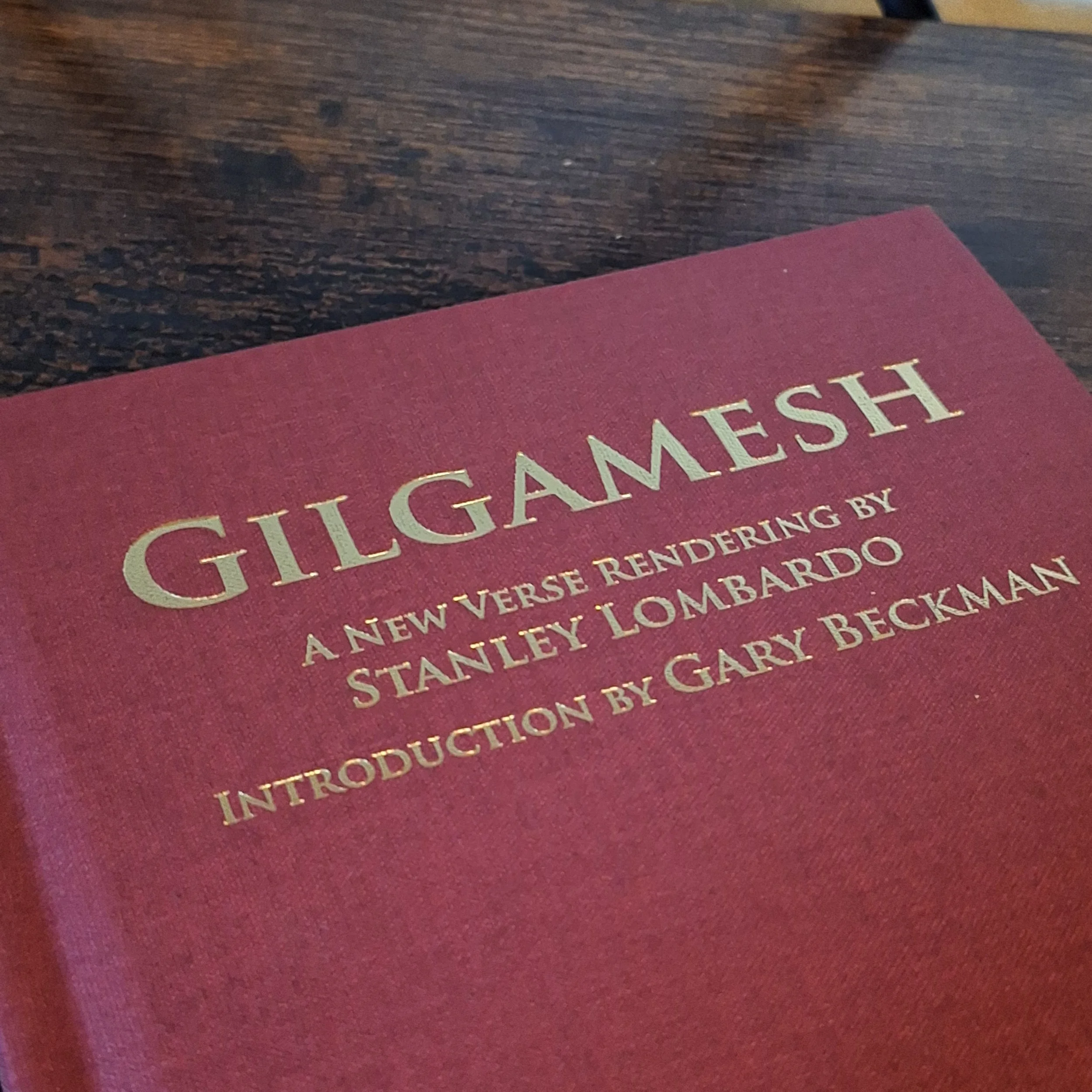

GILGAMESH

Challenge 1: Read any ancient story, written before 476A.D. Try to find a connection with the characters.

The Epic Poem of Gilgamesh is one of the world's earliest forms of fantasy literature, written almost four thousand years ago, around 1800 B.C. The poem combines multiple stories originating as far back as 2600 B.C., bringing Gilgamesh to light for the citizens of Mesopotamia, millennia before great storytellers like Aesop and Homer lived.

The poem includes many story fantasy elements we would recognize today, including a quest for immortality, terrifying creatures, and a litany of gods who often meddle in the affairs of the hapless mortals. It is written in cuneiform, the process of carving mostly wedge-shaped symbols into rock or clay.

Like most Mesopotamian literature, this story was largely forgotten with the rise of Greek and Roman writings. Since its rediscovery in the mid 1800s, fragments of the poem have been discovered, translated, and added, even as late as 2014. The poem was originally told on twelve tablets, each representing another chapter of Gilgamesh's story. The twelfth tablet depicts Gilgamesh in the underworld and is often excluded from publications of the poem. Other ancient stories of Gilgamesh were created, but not all were included in the poem, such as Gilgamesh and Aga.

Speculation of Gilgamesh's actual existence notes the lack of any official documentation about the king. The sole exception is a list of demigods known as the Sumerian Kings List, created long before the poem, around 2100 B.C. Here, the name Bilgames appears, accepted as an earlier version of name Gilgamesh. His rule is recorded as 126 years in length. No other official record of him exists.

What makes this ancient story worth our time thousands of years later? How can we connect with this character, who happens to be one part human, two parts divine, as he confers with gods and goddesses, venturing forth with a companion made from clay, slaying ferocious creatures and questing for immortality?

In spite of, or perhaps because of, his perfection, the citizens of his kingdom appeal directly to the gods for help, as he fights the young men and lusts for women across his kingdom of Uruk. In response, the goddess Aruru creates a being of clay, to be a perfect match and companion for Gilgamesh. Named Enkidu, he will first be “civilized” by the likes of Shamhat the harlot, forcing him to abandon his wild ways as he begins to think like a man instead of a wild beast. Upon meeting, Gilgamesh and Enkidu will fight, as Enkidu attempts to protect yet another new wife from Gilgamesh's advances on her wedding night. Their contest concluded in a draw, they will remain fast friends.

Their adventures begin at Gilgamesh's urging and against Enkidu's wishes, as he tries to establish a name for himself and his friend that will shine for all eternity. For half of the poem they will travel great distances, slay ferocious creatures, and have more dealings with the ancient gods who look on with interest. In this stage, the brash and arrogant Gilgamesh is ready take on any challenge, which includes travelling a month's journey in mere days, slaying the god Enlil's chosen guardian of the cedar forest, Humbaba, spurning the advances of the amorous Ishtar, and defending their kingdom from the Bull of Heaven when the humiliated Ishtar seeks revenge.

In the second half of the poem Gilgamesh has lost his friend Enkidu, whom gods struck with an incurable illness as payment for his part in killing Humbaba and the Bull of Heaven. Struck with grief and a sudden realisation that, like all mortals, his time is limited, he undertakes a quest for immortality. He repeatedly wrestles with his own doubts and fears as he fights a pack of lions, converses with the terrifying scorpion people, and travels through a mountain and into the land of the gods. The people he meets all notice his slovenly appearance, weather-beaten face and gloomy visage, and ask him his business, to be answered the same way each time: he mourns his friend's death, has travelled far and wide, and seeks the key to eternal life from the immortal Utanapishtim. When they finally meet, Gilgamesh is chastised by the immortal, who points out that all he has been doing is hastening his doom, and that death comes for us all in the end. The immortal challenges Gilgamesh to stay awake for six days and seven nights, with eternal life as the prize. The exhausted Gilgamesh is overtaken by sleep almost instantly, though, losing his chance to live forever. He is given an impressive consolation prize at the behest of Utanapishtim's wife: knowledge of a plant that won't grant immortality, but will make those who consume it shed much of their age. Showing ingenuity born out of desperation he digs a channel into the sea, then ties rocks to his feet and crosses the ocean floor to acquire one of these plants. As Gilgamesh and his guide rest on their journey home, a snake snatches the plant and makes off with the prize before he can eat it. Devastated at first, he once again bemoans his fate. As they near Uruk, he points out his kingdom and its glorious architecture to his guide, showing that perhaps he is learning to take pride in more realistic accomplishments and accepting that the smaller things will have to be enough. In the end, a character who is initially not all that relatable is forced to change his expectations to something more realistic.

The king wasn't living with the same everyday stresses we deal with, but he still learned a lesson in humility and was forced to deal with his own failures just as we might. He may, or may not have, lived thousands of years ago, may have been two parts divine to one part human, may have had a chance at immortality, but he showed us that some things about the human condition remain remarkably the same no matter how much time has passed. Thank you, Gilgamesh. For those who are interested, a translation of the poem can be found at www.ancienttexts.org

D.G. Raymond